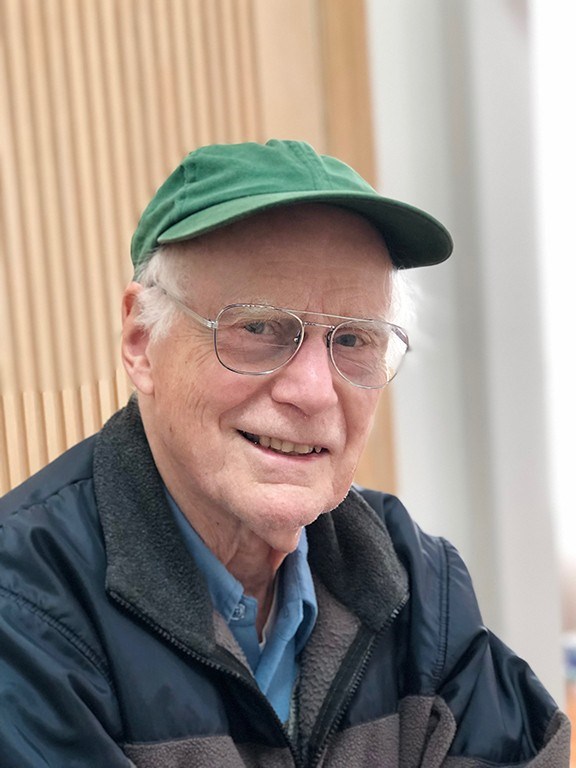

An 86-year-old retired pensioner who inherited his mother’s 1927 home in East Vancouver decades ago says Vancouver’s new empty-homes tax is unfairly forcing non-speculative property owners like himself into either operating a rental business or selling.

The case of Garry Harding’s East Vancouver home is unusual enough that two B.C. real estate lawyers said they have not seen similar complaints since the empty-homes tax came into effect.

Harding, a retired movie projectionist living in Richmond, said he wrote to Vancouver’s municipal government after receiving earlier this year an empty-home tax bill of $14,139, due in April, for his mother’s old house on East 29th Avenue.

Harding’s family has been using the home for storage after inheriting the property, and the house has a number of issues including lead paint and lack of compliance to the fire code that make it “not habitable,” he said.

To avoid the tax – which Harding calls a “punitive, coersive fine” – he would need to spend at least $30,000 to bring it up to code for rental or sell, neither of which he wants to do.

“I sure as hell feel like I’m being cornered,” Harding said. “I’m 86. I’m not going to be able to recoup that money [for repairs] in my lifetime. I don’t think the city can force you to go into business. If you rent a house, you are in the rental business, and you have to get a licence from the City of Vancouver. I don’t want to sell under pressure.”

In a statement responding to Harding’s claims, City of Vancouver spokesman Jag Sandhu said the tax regulations on the issue are straightforward.

“The bylaw that council approved in November 2016 did not exempt uninhabitable properties because the intention is to move forward with creating housing supply on those sites,” Sandhu said.

The city allows an exemption for major redevelopment or renovation, but it only applies to properties that are unoccupied for more than 180 days of the year, where permits have been issued and work is being carried out diligently.

Sandhu said property owners can only submit complaints if the city made an error or the owner did not supply the proper information in his or her property status declaration.

Harding said he is now planning to sell the house by August, and that he feels unduly pressured by the city over the fate of his property.

“We don’t live in a socialist state. Why are we only targeting a specific group of people? If I had housing that’s easily rentable, then I can see that the city would have a case against me. But even then, why do I have to supply housing? If we live in private-enterprise society, why is a gun being put to my head, just because some guy wants to live in Vancouver?”

Wesley McMillan, a commercial litigator with Hakemi & Ridgedale LLP, said the city is within its rights to determine what land in the city should be used for. He added it is the homeowner’s responsibility, not the city’s, to maintain property in habitable condition.

“From a legal perspective, how is this any different than having a house fall into disrepair, and the city issuing a bylaw violation saying the property is an eyesore and a mess, and that the owner has to clean it up or the city will do it and bill the owner for it?” McMillan asked, adding that while the foreign-buyer tax levied by the provincial government has generated some litigation, few have challenged the empty-homes tax – for good reason.

“My thought is, the city clearly has an authority to tax, and they clearly have an authority to dictate land use, and this is a tax to dictate land use,” he said. “So my suspicion is that they are in the clear. The city is not saying you have to sell the thing; they are saying you have to rent it out or sell it. The fact that it has become uninhabitable in the last 16 years – we didn’t tell you to do that. You chose not to.”

However, Ron Usher, a lawyer involved the process of reforming the province’s real estate sector, said people like Harding become “collateral damage” when municipal and provincial regulators try to apply simplistic laws to complex situations.

Usher agreed Harding appears to have little legal recourse, but added that city officials need to look at whether an empty-homes tax that pushes people to develop or sell their property is really helping the situation.

“A compassionate system would look as it this way – is it really accomplishing our goals?” Usher said, noting that the long-existing capital gains tax should already be working as a brake on speculation. “The truth is, this guy [Harding] has a very large tax bill that is coming due. It’s going to get paid.… It’s not like he’s going to get away with something. But we don’t need a new tax.

“Do we really want to push this guy to sell his property to a flip-it speculator? There’s no doubt someone will want to buy this, but is that someone going to build something that’s going to help out our housing situation? Not a chance.”

Usher added that he has seen cases of owners whose homes contain two lots – with one acting as a backyard – and were surprised by new taxes levied because their properties were considered empty homes. He contended that a properly enforced capital tax collection procedure would be far more effective than a new levy that goes after “non-flippers.”

Harding said he is still pondering his next step, including possibly filing a complaint through the city’s ombudsman. But he added that most people he has spoken with supported his position.

He added that, no matter what the demand for housing is like in Vancouver, private owners cannot be forced to accommodate more people.

“They say there are people that want to live in Vancouver,” Harding said. “Well, that’s too bloody bad. I’d like to live in the Beverly Hilton in California, if you want to look at it that way. They say they want to live and work in Vancouver; well, not everyone in the world can live and work in Vancouver.”