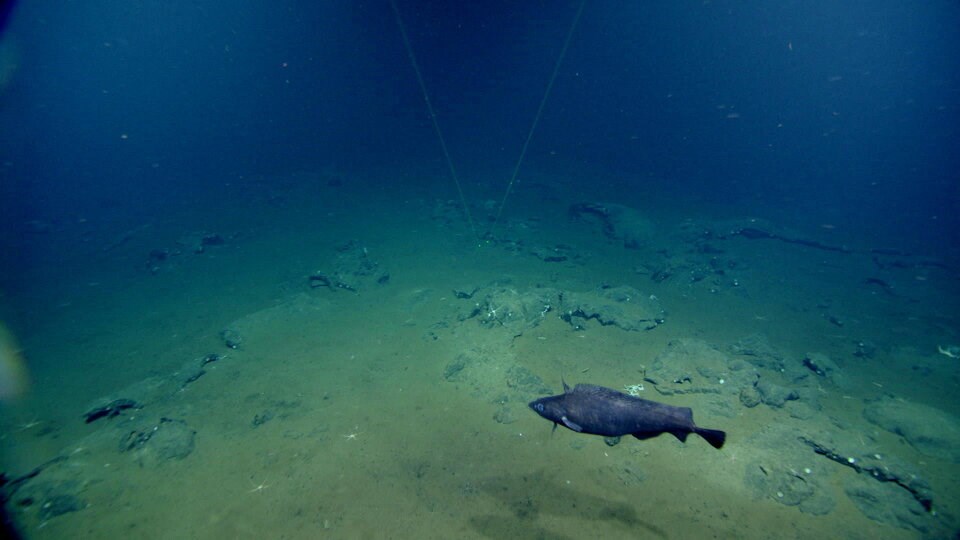

Flat, cold and seemingly devoid of life — muddy seabeds have largely been ignored as Canada moves to double the share of its oceans under protection to 30 per cent of its exclusive economic zone by the end of the decade.

But according to a new study, published Friday in the journal FACETS, those assumptions are wildly off base.

“Blue carbon” sinks — including the world’s mangrove forests, salt marshes and sea grass beds — have become an increasingly popular climate solution for governments and businesses looking to pull carbon out of the atmosphere in the same way trees do.

Out of view of the public, deep, muddy seabeds have rarely been considered, according to Graham Epstein, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Victoria’s department of biological sciences and the study’s lead author.

“Muddy sea floors can sometimes not be as fully appreciated,” said Epstein. “They can be a bit of a harder sell.”

Yet according to Epstein’s calculations, just the top 30 centimetres of Canada’s exclusive economic zone contains almost 11 billion tonnes of carbon. That’s equal to half the carbon stored in Canada’s forests.

The study — which brought researchers together from UVic, Fisheries and Oceans Canada and Oceans North — says when Canada is expanding marine conservation areas, it should consider including more carbon-rich sea beds as deep as 2,500 metres under the surface.

Researchers say bottom-fishing, deep-sea mining, oil and gas extraction, and marine construction all threaten to disturb a biological carbon pump that plays a critical role in removing carbon from the atmosphere.

Carbon pump under threat

Around the world, the top one metre of seabed sediments are estimated to hold around 2,300 billion tonnes of organic carbon — around 200 times more than what’s stored in all coastal vegetation.

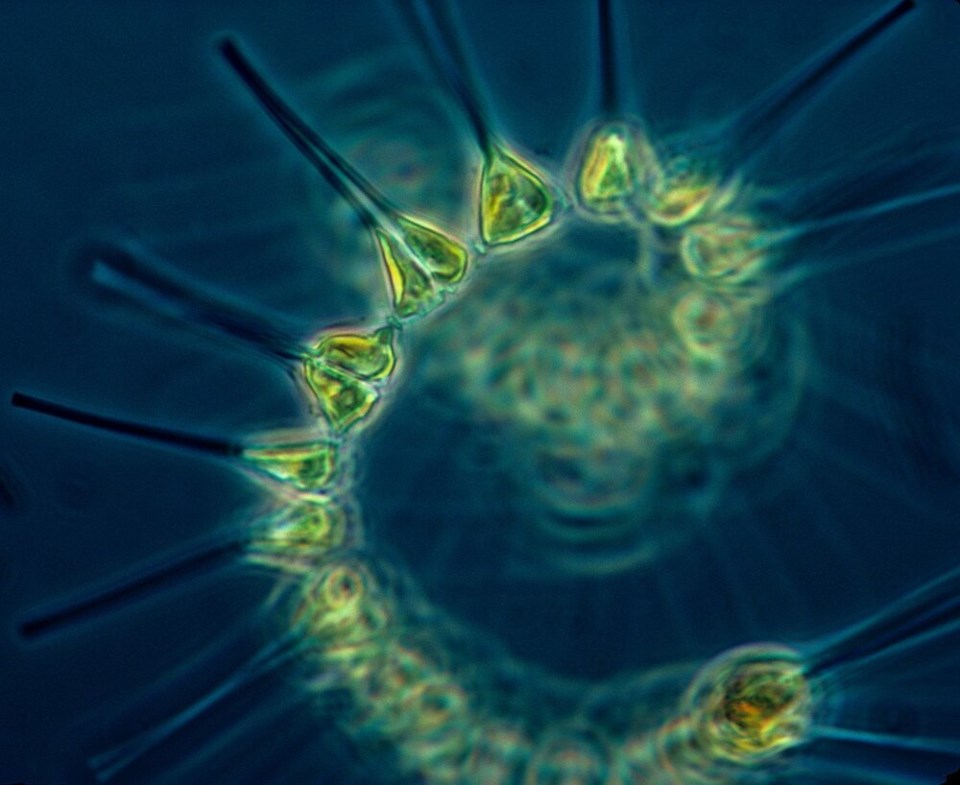

About a third of that sea-floor carbon comes from rivers pouring organic matter into the sea. The rest is from often microscopic creatures that die at sea and later sink to the bottom in a biological carbon pump that cycles carbon dioxide deep into the world’s oceans for up to thousands of years at a time.

By absorbing carbon from the atmosphere and breaking down dead animal and plant matter so it can sink deep into the ocean, microbes and plankton have long acted as one of the lungs of the global climate system. But there are some worrying signs that system is faltering.

Epstein said the amount of CO2 the ocean can absorb from the atmosphere globally is already slowing down because of the effects of climate change.

In 2021, a study looking into the impacts of a marine heat wave off the coast of western Canada found the so-called “blob” threatened to re-order the ocean’s biological pump. As nutrient levels dropped in the warmer water, the size of phytoplankton cells decreased in a trend that could mean less carbon is getting scrubbed from the atmosphere.

Any activities that disturb carbon buried on the ocean floor would mix it back into the seawater. And that could limit the ocean’s carbon-sucking powers even further, said Epstein.

“It could slow the ocean’s abilities to continue to absorb carbon,” he said.

274 carbon hot spots found on Canada's sea floor

Because of the size of the deep sea, most of the ocean’s total carbon stocks are far from the coastline.

At the same time, about 85 per cent of the ocean’s accumulation of sea-floor carbon occurs on the continental margins, where biological matter flows from the land into fjords and deltas.

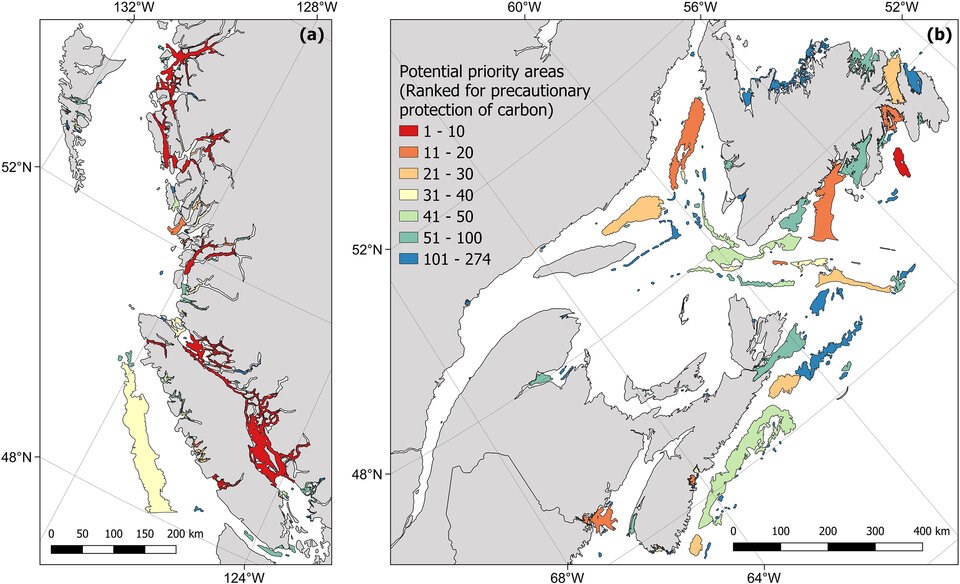

Epstein said more research needs to be done to figure out which areas to protect. As a starting point, he found and ranked 274 marine areas that could be prioritized based on ecological significance and the amount and vulnerability of carbon stored there.

The highest-priority areas in B.C. included many of the fjords and inlets on the west coast of Vancouver Island and the province’s mainland, as well as Queen Charlotte Strait and northern Salish Sea.

On the east coast, the study highlighted seabeds off New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Newfoundland and Labrador.

Canada has the seventh-largest exclusive economic zone in the world. Given that large area, Epstein said that gives it an outsized influence over how much sediment carbon it can protect within its jurisdiction.

Any human activity — including dredging, mineral extraction, offshore energy projects, deploying undersea cables and bottom fishing — can disrupt those deposits.

“Protecting important areas of seabed sediment will help to ensure that the carbon stays buried, rather than re-entering the carbon cycle and contributing to climate change,” Susanna Fuller, vice-president of conservation and projects at Oceans North, said in a statement.

Study warrants new look at carbon hot spots

Kate Moran, CEO of Ocean Networks Canada, said we should be careful not to overstate how much carbon can be unlocked from the seafloor due to human activity — especially in a jurisdiction like B.C., where some forms of bottom trawling have been banned.

However, Moran agreed with Epstein and his colleagues that more protections need to be placed in coastal areas where industrial activities, like dredging, might overlap with high concentrations of seafloor carbon.

“We are an imperfect species. We do things to keep populations safe. In some ways, dredging is important to prevent ships from going aground and spilling oil,” Moran said.

“But taking a precautionary approach, it would be useful to take a look at these activities and assess them for the risks and benefits — especially now that they’re identifying that we could be releasing carbon by some of these seafloor disturbances.”

B.C. waters a target for carbon burial

In 2024, global average temperatures approached and may have exceeded 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming above pre-industrial levels — a threshold that caught many scientists by surprise.

As the planet heats up, Moran said removing the carbon already added to the atmosphere is growing more important at a time natural carbon sinks can’t keep up.

That thinking led her organization, Ocean Networks Canada, to join Columbia University, the University of British Columbia, and the Pacific Institute for Climate Solutions to launch Solid Carbon, a project that aims to mechanically scrub carbon from the atmosphere and bury it in the sea floor.

The project proposes to build direct air capture technology on floating ocean platforms. From there, the wind turbine-powered facility would inject the captured CO2 through pipes and into basalt rock deposits under the seabed, where within a few years, the gas would turn to stone.

Moran says they hope to float the platform about 200 kilometres off the west coast of Vancouver Island, where the seabed has the potential to store up to 15 years of global CO2 emissions, according to a recent feasibility study.

On land, many oil and gas companies are pumping carbon into pressurized rock deposits that once held fossil fuels. That requires near indefinite monitoring.

Solid Carbon’s proposed operation, on the other hand, requires much less energy and only a few years of oversight while the gas turns to stone, according to Moran.

The project proponents are seeking $60 million and regulatory approval to carry out a large demonstration in an already protected marine area off Vancouver Island.

“It’s feasible,” said Moran. “We’re putting it back where it belongs.”

CORRECTION: A previous version of this story stated all forms of bottom trawling have been banned in B.C. In fact, the province still has active groundfish and shrimp trawl fisheries, and a small scallop dredge fishery.